Both cameras and imaging technologies have advanced rapidly in the last few decades, leading to the production of some fascinating images. As a result, the visual impact of the images associated with research on humans attracts a lot of interest. Here we go through some of the technologies used that have been found to be extremely useful in skin care research and still hold huge potential for further developments.

3D Imaging

Nowadays, a number of systems are available for the clinical practice or for researcher using 3D imaging technology. Coming in either handheld or fixed varieties, there are a number of ways to generate 3D imaging – multiple cameras linked to fire simultaneously, a singular camera as part of a turntable system, or a laser scanner that builds a true 3D topographical map of the skin. All these methods allow for quick and accurate capture of a 3D body or face image. They are also reproducible as subjects’ distance and lighting conditions are standardised within the apparatus and do not vary across multiple visits.

These systems have many applications in cosmetic practice. Analysis of the skin or body before and after cosmetic procedures can occur, with some treatments being informed by the results of the initial analysis. 3D cameras have also been adopted in studies involving topical preparations for the objective assessment of the effects on skin topography (lines and wrinkles, skin puffiness, acne, scars etc.) which provides an extra level of accuracy that is not possible using traditional 2D methods.

UV Cameras

Ultraviolet (UV) light is a form of light emitted by the sun that is invisible to the human eye. It occupies the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum between X-rays and visible light. Most part of the UV light is absorbed by the earth’s ozone layer. In fact, UV light constitutes about 5% of terrestrial sunlight. There are three types of UV rays – A, B, and C, with increasing penetrative ability and risk for harm.

Although UV has some important benefits for humans such helping improve mood, triggering vitamin D (which in turn helps strengthen bones, muscles and the body’s immune system), and helping some skin conditions such as psoriasis, in more recent years, great emphasis has been given to the harmful effects of UV such as skin ageing, sunburn and skin cancer. UV related skin damage is a widespread issue. Australia has one of the highest rates of skin cancer in the world, in which UV radiation is attributed as the main preventable cause. As such, formulating efficacious and protective sunscreen products is vital for both the consumer and pharmaceutical markets.

While the levels of sunscreen ingredients present will obviously have an impact on the overall protection capability of the product when applied to skin, an area which is often overlooked is formulation from which these ingredients are being delivered, and the impact it has on how the sunscreens spreads and moves on the skin once applied. Studies use UV reflectance photography to assess how the sunscreen spreads across the body, both directly after self-application and after a period of use. The spreading of the sunscreen ingredients will have a dramatic impact on the overall protection offered by the film, as areas of the applied film where the layer is thinner will more readily allow an increased level of UV light to penetrate and damage the skin.

Another popular application for UV photography is analysis of UV skin damage. In fact, this type of application has been shown to a have a positive impact on individual skin health and protection behaviours. A randomized clinical trial in university students showed that a UV photography intervention resulted in significantly stronger sun protection intentions (P < .01) and greater sun protection behaviours (P < .05). These findings demonstrate the importance of broadening the use of UV photography to improve skin health.

Infrared Cameras

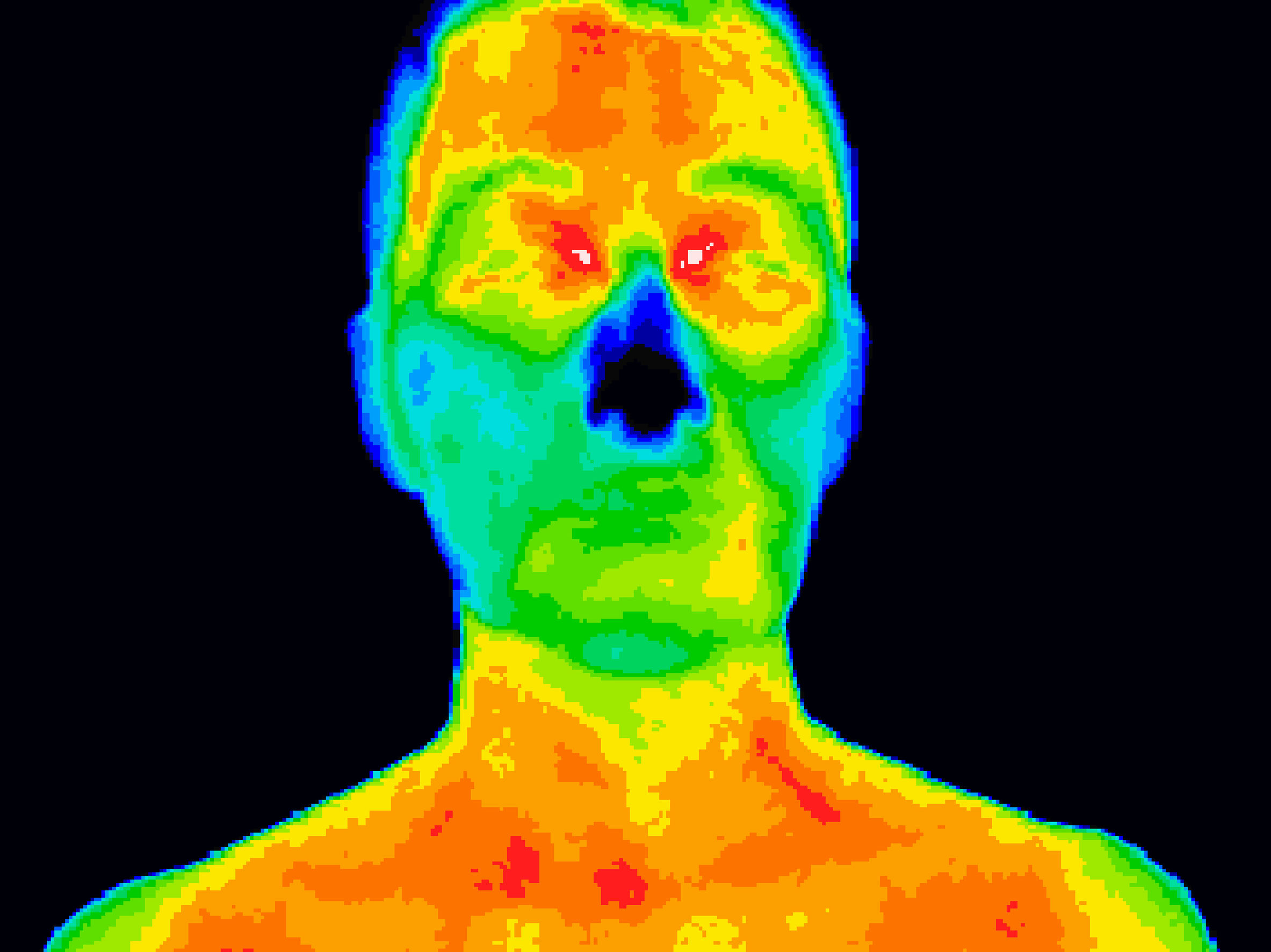

Infrared radiation is radiation with longer and less energetic than visible light, and transmits heat over long distances. Thermography, or thermal imaging, uses a special camera that is able to measure these waves, and thus the temperature of objects, surfaces, and living organisms. The difference between the values of temperature traditionally measured with contact probes (the standard technique) and the ones measured by thermal imaging lies in the fact that the former produces a singular value based on the contact point, while the latter gives a distribution over a continuous area, producing 2D heatmaps.

Thermography imaging does not involve ionizing radiation – it is fast and non-invasive. For these reasons, it is used in diagnostic medicine for detecting, recording and producing infrared images that reflect the microcirculatory dynamics of the skin surface of individuals in real time, comprising the vascular, nervous and musculoskeletal systems, in addition to inflammatory processes, as well as endocrine and oncological conditions.

In healthy subjects, the hypothalamus homogenises skin blood flow using the central nervous system in order to maintain normal thermoregulation. This results in a symmetrical thermal pattern between the right and the left side of the body. On the other hand, qualitative and quantitative changes in thermal distribution are indicative of abnormality. This principle can be applied even on smaller scales – anomalous skin function can be detected by the presence of unusually hot or cold patches on the skin. There are many other uses for thermography, such as: in dental imaging; diagnosing specific pathologies; as an indicator of the muscle activity during physical exercise; post-surgery monitoring skin grafts to identify positive blood flow in the new flap of skin, and so on.

In scientific studies assessing the effects of topical preparations, thermography has most recently been used to investigate the stimulation of cooling effects and blood flow increases in the areas of the skin treated with the study product.

————–

References:

http://www.thecosmeticchemist.com/education/skin_science/uv_photographic_imaging.html

Karimkhani C, Huff LS, Dellavalle RP, Measuring sun damage at the grocery store: Mychelle Dermaceuticals and Whole Foods Market bring UV photography to aisle #7, JAMA Dermatol. 2014 Jun;150(6):589-90

Miguel A, Santiago R, Meritxell V, Jorge A. H, Xana D, Ferran S, Handheld 3D Scanning System for In-Vivo Imaging of Skin Cancer, 5th International Conference on 3D Body Scanning Technologies, Lugano, Switzerland, 21-22 October 2014

Denise S Haddad, Marcos L Brioschi, Marina G Baladi and Emiko S Arita, A new evaluation of heat distribution on facial skin surface by infrared thermography, Dentomaxillofacial Radiology (2016) 45, 20150264

N.Ludwig, D.Formenti, M.Gargano, G.Alberti, Skin temperature evaluation by infrared thermography: Comparison of image analysis methods, Infrared Physics & Technology Volume 62, January 2014, Pages 1-6

Reena Murthy, S.Rangappa, Michael A.Repka, K.Vanaja, H.N.Shivakumar, S. Narasimh, Murthy, Infrared thermal measurement method to evaluate the skin cooling effect of topical products and the impact of microstructure of creams, Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology Volume 39, June 2017, Pages 296-299