Wound healing is an ‘imperfect’ process, inevitably leading to scar formation. The resulting scars have different characteristics to normal skin, ranging from fine line asymptomatic scars to problematic scarring including hypertrophic and keloid scars. Scars can appear as a different colour to the surrounding skin including red scars and scars that are darker than the rest of the skin. They can be flat, stretched, depressed or raised, manifesting a range of symptoms including inflammation, erythema, dryness and pruritus, which can result in significant psychosocial impact on patients and their quality of life. Scars can result from dermal injury due to disease and trauma and some common examples include burn scars, acne scars and surgical scars.

SUBJECTIVE ASSESSMENT

To assess the evolution of scars over time, a number of subjective rating scales have been introduced into clinical practice. These scales can be obtained free of charge or for a small fee and require minimal training to utilise. For example, the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) was developed in 2002 for the assessment of all different types of scar tissue. The POSAS enables a structured clinical evaluation of scar quality. Assessments are conducted by both patient and clinician independently.

The scale contains questions applying to pain, itching, pigmentation and vascularity, pliability, thickness and relief. Each of the questions has a 10-point score, with ‘10’ indicating the worst imaginable scar or sensation. The lowest score is ‘1’, and corresponds to the situation of normal skin (normal pigmentation, no itching etc.). All questions add up to the ‘Total Score’ of the Patient Scale and Observer Scale respectively. Besides the main questions, patient and observer are asked to provide an ‘Overall Opinion’ concerning scar quality, which is scored separately.

However, scar scales like POSAS are considered to be subjective and the resulting scores can vary between different assessors (inter-assessor variation), different scar severities and age of the scar. Some studies have suggested that more than one assessor is required in order to produce reliable ratings and then taking the average. The POSAS attempts to improve the method of rating scars by including the patients’ perspective; however, patients’ perception and subjective evaluation of their scars have been shown to be influenced by depressive symptoms. Moreover, the physical characteristics of scars make rating quite difficult. For example scars are rarely homogenous in both colour and texture, which makes estimation of mean values difficult and inaccurate for a human observer.

To monitor changes in scar quality over time and determine the effectiveness of scar treatments it is therefore necessary to utilise additional objective assessment tools which are standardised, quantifiable, reproducible and validated.

OBJECTIVE ASSESSMENTS

There are several objective measures that relate to scar severity including:

Colour: erythema and pigmentation contribute significantly to the appearance of a scar.

Dimensions: including the surface area, thickness and volume.

Texture: surface texture or scar roughness has a significant effect on the patient’s and observer’s opinion of the scar.

Biomechanical properties: pliability and elasticity. Stiffness and hardening of scars are due to increased collagen synthesis and lack of elastin in the dermal layer and can lead to impairment of skin function, especially when the scar is located around joints.

Other skin parameter: including transepidermal water loss and moisture content.

Tissue microstructure: new non-invasive in vivo imaging techniques are able to analyse the morphology of the scar, providing measurements previously only possible by histopathological analysis of biopsy samples.

Scars following injury or surgery are often treated with self-medication independently of clinician care. Patients only seek diagnosis and treatment, should signs and symptoms worsen, such as in the case of hypertrophic and keloid scarring, which may require a more appropriate intervention. Several prescription and over-the-counter topical remedies are available on the market, which claim to improve the appearance of scars and accelerate the rate of wound healing. Topical treatments have the advantage of constant skin adhesion and localised product delivery.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW FOR SCAR TREATMENT OPTIONS

Several large systematic reviews have been published, with regards to treatments available for various types of scars. The main conclusion drawn from these reviews was that while several options are available for treatment of a range of different scar types, there were no large scale studies with prolonged follow-up periods to draw firm conclusions regarding long-term efficacy. Other common problems were poor randomisation and blinding, the range of different scar assessment methodologies used and varied outcome measures reported. It is difficult to randomise a trial based on wound healing because of several variables to take into account. Many factors such as anatomical location, patient demographics and medical history, surgical operation performed or the age and type of scar, the injury that caused it and the lack of controls, make it difficult to standardise between trials. Despite the volume of research into treatments for skin scarring and some positive evidence presented, we don’t know how many trials showing negative results are not published and therefore are not available for review.

OUR FINDINGS IN A RECENT STUDY

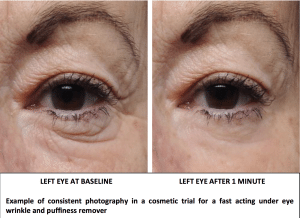

In an independent study we have recently completed on scars treated with a topical cosmetic preparation interesting results on the efficacy of the product have been obtained. This open label study aimed at comparing scar appearance after 4 weeks and 8 weeks of treatment compared to baseline. A combination of objective and subjective assessments were used, including digital photographs, image analysis of silicon replica, a general questionnaire regarding sensory, quality and safety of the product and the POSAS. In this study statistically significant reductions compared to baseline were found in the scar total area, length, and roughness at each time point. This was evident in some of the digital photos taken and the POSAS (patient assessment only). Better results were reported in younger scars as opposed to older scars. Although this study did not have a control, it indicated some promising results with regards to use of topical preparation for scar improvement.

Scars are a result of the natural skin healing process. There is some evidence suggesting that topical preparations may assist the natural process by helping the scar improving faster and better. More clinical trial data is needed to increase the level of evidence in support of topical treatments in comparison with other approaches. The adoption of objective assessments and appropriate study design including a control, randomisation and sample size calculation, will improve conduct of studies that may confirm the potential of topical treatment to improve the appearance of scars.

References

- https://www.dermcoll.edu.au/atoz/scar-treatments/

- http://www.bodyandsoul.com.au/beauty/body/reduce-the-appearance-of-scars/news-story/1bba2e5fc889b4813e114ad407fabfec

- P. Sidgwick, D. McGeorge, and A. Bayat, A comprehensive evidence-based review on the role of topicals and dressings in the management of skin scarring, Archives of Dermatological Research 2015; 307(6): 461–477.

- Kwang Chear Lee, Janine Dretzke, […], and Naiem Moiemen, A systematic review of objective burn scar measurements, Burns Trauma. 2016; 4: 14