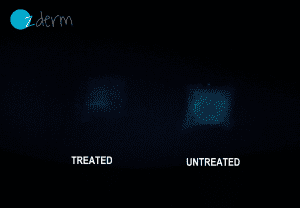

With the temperatures warming up in summer, shorts and swimming costumes become more prevalent options for the beach or pool, exposing a very common aesthetic skin concern – cellulite. It is a sad fact that digitally altered photos in the media (like the one attached!) are becoming increasingly more prevalent, and have thus influenced the perception of beauty by providing unrealistic ideals. Such images deceive the general public about the true prevalence of cellulite and reinforce the idea that smooth, flawless skin is normal.

Cellulite is characterised by the formation of lumps and dimples in the skin due to fat deposits. It is usually present on buttocks and thighs, although it can occur on other parts of the body. Cellulite is a multifactorial condition that can affect both men and women, but it is more common in females due to the different distributions of fat, muscle, and connective tissue. In fact, it is estimated that cellulite occurs in 80% to 90% of females after puberty.

Quantifying and assessing cellulite

The main challenge in assessing the efficacy of anticellulite products and procedures is the lack of a precise and reproducible method for quantifying cellulite. Some methods have been considered either not precise enough (e.g., stereoscopic systems) or use a measurement field that is too small to capture the whole cellulite pattern (e.g., fringe projection systems). As a result, various techniques have been developed to measure cellulite indirectly. One such technique involves comparing thigh circumference measurements before and after treatment. The downside is low reliability as well as the fact that reduction in circumference, is not proven to correspond with a decrease in cellulite severity. The use of calipers, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or X-ray imaging also have been found to have similar issues.

Other options are to evaluate change in cellulite are measurement of skin elasticity, dermal thickness or density measurements. Although their importance in skin ageing has long been established, the correlation between these parameters and cellulite is unclear. The same has been said with regards to assessing blood flow or vascularization by laser Doppler velocimetry or thermography. Therefore, despite all efforts to make cellulite assessment more objective through qualitative and quantitative measurements, to this day, the subjective clinical assessment of cellulite remains the most appropriate option.

In 2009, a severity scale to assess cellulite was developed as follows:

Grade 1, or mild: There is an “orange-peel” appearance, with between 1 and 4 superficial depressions, and a slightly “draped” or sagging appearance to the skin.

Grade 2, or moderate: There are between five and nine medium-depth depressions, a “cottage cheese” appearance, and the skin appears moderately draped.

Grade 3, or severe: There is a “mattress” appearance, with 10 or more deep depressions, and the skin is severely draped.

This scale includes four clinical morphologic features of cellulite: the number of evident depressions, the depth of the depressions, the morphological appearance of skin surface alterations, and the grade of laxity and flaccidity (sagging skin). Even though the scale is validated and comes with a set of pictures illustrating each morphological feature, the clinical rating of cellulite is not easy. Further complicating issues, the process of taking standardized photos of cellulite is difficult and might require special equipment with specific room conditions for optimal performance.

Treatment options

In 2015 a review was conducted to provide a systematic evaluation of the scientific evidence of the efficacy of treatments for cellulite reduction with the view to identify possible benefits and limits of each.

1) Mechanical Stimulation

One of the oldest methods of cellulite treatment is mechanical tissue stimulation. This involves lymphatic drainage of the skin, which is either performed manually or with an assisted device. However, the efficacy of mechanical tissue stimulation in the treatment of cellulite is not clear. Though an improvement in cellulite grading and a reduction in thigh circumference was observed after device-based deep tissue massage in most of the studies, none of these studies compared mechanical tissue stimulation with a placebo or an untreated control, meaning the cause(s) of the reduction cannot be inferred.

2) Topical products

Topical cosmetic preparations are among the most commonly used methods to reduce the unwanted appearance of cellulite. Most anti-cellulite products contain ingredients that may have an effect through lipolysis of the adipose tissue, the stimulation of the peripheral microcirculation to facilitate lymphatic drainage, and the reduction of oedema. For example products containing caffeine, and/ or retinol formulations, and/or botanical derivatives (e.g. Gingko biloba, Centella asiatica, and horse chestnut) as the main active ingredients.

Despite the promising formulations, the review unfortunately concludes there is little evidence that topical treatments have a potential positive effect on the appearance of cellulite. Most of the studies suggest that the treatment has either no or non-significant efficacy compared with baseline or compared with a non-active topical treatment.

3) Acoustic Wave Therapy

Shock waves are high-amplitude acoustic longitudinal pressure waves that transmit energy from the point of origin to the therapy regions. While in the 1980s, high-energy, focused extracorporeal shock waves were first used for the lithotripsy fragmentation of kidney stones, today, less powerful acoustic shock wave therapies (AWT) have been introduced as a treatment option for cellulite. It is supposed that AWT may improve local blood circulation and increase cell proliferation of collagen and elastin fibers to improve skin elasticity and to revitalize the dermis. AWT may also have a positive effect on lymphedema by promoting lymph transport, which is a pathway often associated with cellulite.

Although more studies are needed to further evaluate the ability of AWT to treat cellulite, there might be some evidence that suggests AWT has good efficacy.

4) Laser- and Light-Based Devices

Non-invasive long-pulsed lasers (longer wavelength lasers) such as 1064 nm Nd:YAG or the minimally invasive 1440 nm Nd:YAG laser have been used in the treatment of cellulite. These lasers deliver thermal energy into the deep dermis and the hypodermis to generate a wound-healing response that promotes the formation of new collagen. Low-level lasers (operating in the milliwatt power range) can also be used to treat cellulite. However, unlike common high-energy lasers, lower energy beams do not cause significant skin heating.

From scientific studies, not all laser and light based approaches produce the same level of results. In fact, there is very little evidence that the non-invasive use of 1064 nm Nd:YAG lasers is effective. Additionally, the efficacy of low-level lasers is unclear, as study results are conflicting. However, the minimally invasive 1440 nm lasers seem to significantly improve the clinical appearance of cellulite, decrease dimple depth, the number of dimples, and smoothen the contour of the skin, although consistent reproducibility of these results is still pending.

5) Radiofrequency

Radiofrequency (RF) waves are often used to treat cellulite. It has been suggested that heating skin with RF energy leads to a thermally mediated reaction in the dermis associated with collagen denaturation, followed by tissue tightening. A variety of RF devices are used to treat cellulite that vary based on power (high- and low-RF) and whether they combine IR radiation and/or massage.

The evidence on the effectiveness of high-level RF and RF combination therapy for treating cellulite is low. In fact, for the reviewed studies, either no valid statistical analyses were provided, or the results did not show significant treatment success. Only one low-level RF randomised controlled trial showed significant improvement in cellulite appearance after the treatment. In summary, more double-blind randomised controlled trials with larger sample sizes are necessary to confirm these results.

6) Other methods

Additional cellulite treatments have been evaluated and published in scientific journals on the topics of weight loss, nutritional supplements, minimally invasive subcision, carbon dioxide (CO2) therapy, occlusive compression stockings, phonophoresis with hyaluronidase, as well as collagenase injections. Overall, the efficacy of these options is not supported by solid scientific evidence.

Conclusion

Although a multitude of treatments have been developed to improve the appearance of cellulite and achieve a smoother skin surface, a literature review of the studies investigating cellulite removal cannot confirm or deny the efficacy of any such technique. While there are many methods available, the treatment of cellulite continues to be a challenging issue. More randomised controlled trials with high-quality trial design, more subjects, and proper statistical analysis are needed to confirm the anecdotal evidence and claims that have been made regarding cellulite removal.

References

Neil Sadick, Treatment for cellulite, International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, Volume 5, Issue 1, February 2019, Pages 68-72

Peter Crosta, Everything you need to know about cellulite, Medical News Today, November 30, 2017

Hexsel, Doris & Dal’Forno, TD & Hexsel, C. (2009). A validated photonumeric cellulite severity scale. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 23. 523-8. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03101.x.

Luebberding, Stefanie & Krueger, Nils & Sadick, Neil. (2015). Cellulite: An Evidence-Based Review. American journal of clinical dermatology. 16. 10.1007/s40257-015-0129-5.